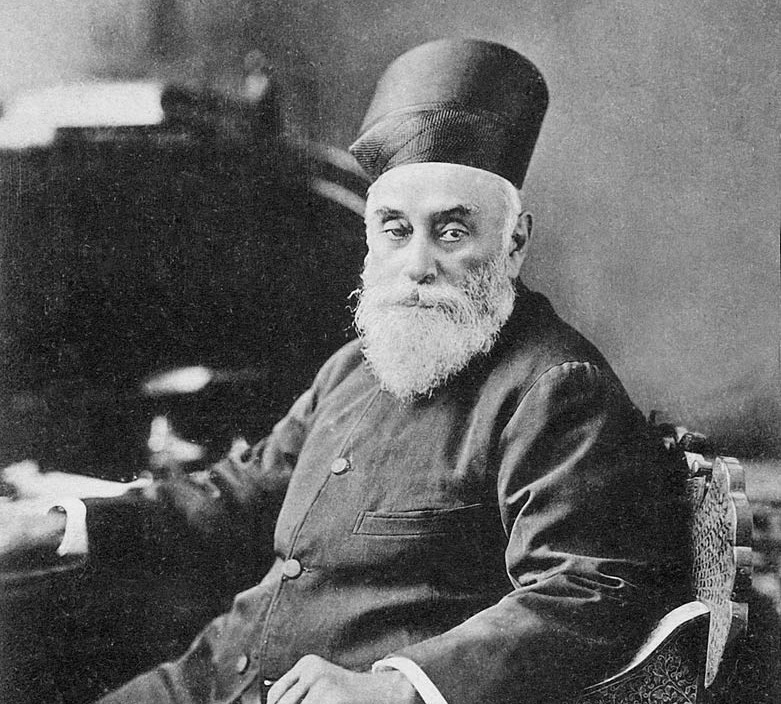

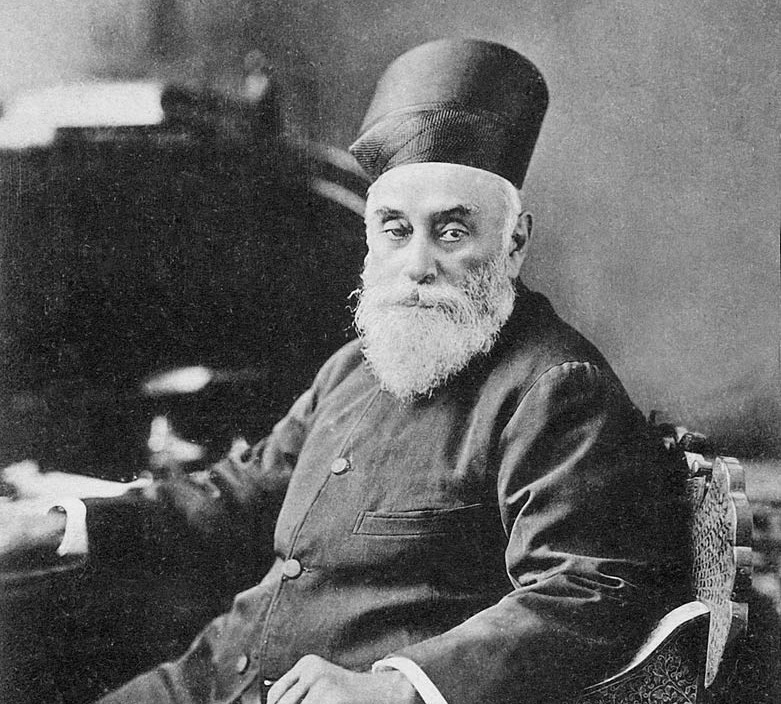

The remarkable life story of Jamsetji commands greater respect for the Tata patriarch, who worked tirelessly to industrialise India and contributed more value than could have been accumulated over centuries by many entrepreneurs combined. Today, Tata Steel is the largest steel producer in India and among the ten largest in the world. At the heart of its foundation was the dream Jamsetji had nurtured since he was 43 years old, after reading a report by Ritter von Schwartz, a German geologist, about an iron ore deposit in Central India. He worked for over two decades but died three years before Tata Steel was able to establish its site.

Recently, my father advised me to read “The Creation of Wealth: The Tatas from the 19th Century to the 21st Century” by Russi M. Lala, a Tata historian and a journalist. I read the e-book version of it under compulsion and so much pestering by my father. Though reluctantly at first, I began to read, which later inexplicably impressed me, and I found it to be worth the effort. It was informative and inspiring, I admitted after reading the book. One would never get such knowledge in a classroom, I am sure.

I found every page from JRD Tata’s Foreword and RML’s Preface to the epilogue by Ratan Tata, raising my enthusiasm to know what was next. The book unravelled an incredible story of the Tatas’ struggle to build a steel mill and more through the periods of British India and Independent India! I was awestruck by the patience, perseverance and determination that the illustrious Tata patriarch had shown while travelling from continent to continent, meeting geologist after geologist and British master after master in pursuit of his dream to build steel mills, coal mines and more.

Tata’s prominence in India’s industrial landscape for over one and a quarter of a century came not without great pains and tolerance. The Tatas could have done better for India had the lawmakers and bureaucrats of post-independent India been kind enough to support all their proposals, considering them for the better future of India. There were times when the Britishers were astonished by the vision of Jamsetji for India’s industrialisation. He had a burning passion for building large industries to make India self-dependent, and he worked hard, adhering to his principles. The Tatas never compromised on ethics for business growth. Once JRD Tata replied to some questions of the book’s author: “What would have happened if our philosophy was like that of some other companies which do not stop at any means to attain ends…. If we were like other groups, we would be twice as big as they are today. What we have sacrificed is 100 per cent growth.” Nevertheless, Tata continued to grow and make its mark in the industrial and social landscape of India, and over a period in the global market.

Jamstji’s successors, Dorabji Tata, Nowroji Saklatwala, JRD Tata, and Ratan Tata, inherited his dream and contributed their best to build the business empire. Jamsetji worked relentlessly and untiringly despite knowing his dream of building a steel mill after exploring mines was far away. Once, he told his cousin R D Tata, “If you cannot make it greater, at least preserve it. Do not let things slide. Go on doing my work and increasing it, but if you cannot, do not lose what we have already done.” Jamsetji, an ardent nationalist, had many dreams – great dreams for India that our three generations sadly missed, but the successors of the Tatas from Dorab Tata to Ratan Tata built the empire brick by brick, keeping the true Tata tradition of integrity and ethical standards. Ratan Tata made the name Tata a global name by buying out foreign brands that were perceived as impossible for Indian companies until then.

The Tatas have shown extraordinary resilience to economic shocks, lukewarm government support and market competition. In the 1990s, many business watchers had discounted Tata’s ability to preserve its business leadership and prominence. But they corrected their notion after Ratan Tata stepped in. When he was put to choose between the necessity of taking care of his mother and planning out for the Tatas immediately after his anointment, he chose both, indicating his ability to balance the two challenges. When TOMCO and Lakme went out of the Tata fold, Ratan Tata captured bigger territories and established a global presence.

Every Indian admires top industrial conglomerates, industrialists and businessmen for their efforts to change the lives of millions and make the country proud during both the pre- and post-British industrial revolutions. The Tatas are certainly one of them. Their legendary vision, remarkable resilience and strict adherence to ethics are beyond description. While some industrial houses have collapsed due to mismanagement, corrupt business practices, and shortcuts, those that have survived and thrived over generations have become great institutions in their own right.

Swadeshi Mill faced difficulties when its share prices dropped significantly after a shipment was rejected. When banks refused to extend a working capital facility to the company, Jamsetji sold his assets to recapitalise it. Once Sir Dorab Tata said about his father, Jamsetji, the founder of the Tata empire, that today every Indian is proud of: ‘The acquisition of wealth was only a secondary object in life; it was always subordinate to the constant desire in his heart to improve the industrial and intellectual condition of the people of this country.” Tata represents modern India’s aspiration and entrepreneurs’ patriotism and passion for ‘Make in India’. It is not just an industrial group to make a profit, but an India that always dreams big and works constantly to improve everyone’s life. The group’s patriarch had the dream not only to build steel and textile mills but also green power plants and world-class educational institutions. His successors had visions to complement his dreams by bringing their business ideas. However, many times the leaders within the Tatas faced lukewarm responses from the government in the 1960s, enough to dampen their morale.

Darbari Seth of Tata Chemicals conceived a unique fertiliser project in Mithapur in 1967. The futuristic agro-industrial complex was designed to have a sloar-cum-nuclear power project. The implementation of the project had the potential to save billions of rupees in foreign exchange from consistently rising fertiliser import liabilities India faced. The project excited Indira Gandhi (who became Prime Minister the previous year) when she visited the project site. However, a coccus within her office resisted support for the proposals, supposedly to benefit foreign companies!

That was the second major shock the Tatas were struck with after Sumant Mulgaonkar of Tata Engineering and Locomotive Company (TELCO) – now Tata Motors got a no nod for its plan to build a production facility for Mercedes-Benz passenger car in India. TELCO was making Daimler lorries under an agreement with Mercedes-Benz. The company established a manufacturing facility in Jamshedpur for Daimler, and Mercedes-Benz was pleased with TELCO’s performance. In 1960, a highly satisfied German auto giant wanted TELCO to manufacture the Mercedes-Benz 180D Model at its Jamshedpur plant. After that, Mulgaonkar met with senior bureaucrat K.B. Lall and handed him the keys to six models. He provided these for one year to determine whether the government would allow him to manufacture the car in India. Krishna Menon, then India’s Defence Minister, used one of the cars that came free for a year. After a year, all the keys were returned to the Tatas, leaving along with them no feedback or response. The government’s lethargy might have embarrassed the Tatas, but it might be one of several such embarrassments the Tatas faced.

The Tatas survived through hostile and tumultuous times, fought against all odds with great wisdom and risked their hard-earned wealth with great optimism. At the age of 59, when Jamsetji began to work on a steel plant, his long-time dream, neither the British state secretary nor Lord Curzon had confidence in its success. The project required decades of flowing rivers of sweat, risk capital, and the right people to dig the ground and make the factory fences. India then did not have all these, and not many did have a vision that Jamsetji cherished. The English ruler would not encourage an Indian beyond local trading, making silk yarns, farming and planting spices. Jamsetji’s story of superior sagacity provides an emulable lesson that is inspirational, too.

In the Foreword, JRD Tata wrote: In congratulating Russi Lala on the initial and well-deserved success of his work, I hope that the young people who read it will find in it some inspiration in pursuing successful careers in which the knowledge that they are contributing to the country’s progress will be one of the most satisfying rewards.

Jamsetji never bothered about success and failure, even in unfavourable atmospheres. The British were narrow-minded when they dealt with India’s industrialisation. Jamsetji had a vision for India; he fought against obstacles and was bold enough to offer his properties worth ₹30 lakh in 1898 to establish a science university that he found “key to India’s modernisation.” The British rulers refused permission. Lord Curzon did not take it seriously because there were no prospects for students who passed out of such an institution. While refusing the permission, the British authorities advised him to use his wealth to build hydroelectric power and steel plants. Today, Tata is a steel behemoth in the world and a leader in India’s private power sector.

When the highly prejudiced P&O Line charged excessive freight for Indian exports to the Far East, Jamsetji started the Tata Line with the Japanese shipping firm, Nippon Yusen Kaisha, famously known as NYK. The prejudicial and discretionary practices of P&O favoured the British and Jewish cotton traders. However, after Tata entered the shipping segment, P&O Line had to shift its gears and began to offer freight-free cotton shipments to the Far East. That resulted in the fledgling Tata Line losing its business and eventually closing it. The history of the legendary Tata family exemplifies how the remarkable perseverance and vision of Jamsetji nurtured an industrial empire that now commands international respect and a significant presence.

The Tatas could have changed India decades ago had their plans and projects been allowed to be built. Jamsetji had great visions. A lover of picnics and boating trips, one day, when he was on a boating trip, he saw rainwater gushing from the Roha River. He was unhappy with the scene. “All this water from the Western Ghats is wasted. We should harness it to produce hydroelectric power,” he felt. He also envisaged creating a reservoir on the brink of the Western Ghats and letting the water gush through pipelines to turn the turbines. He felt the hydroelectric power generation would rescue Mumbai (then Bombay) from the smoke and soot released by the coal-burning textile mills of Bombay. However, before the Tata Hydroelectric Power Supply Company was established, Jamsetji died.

When Jamsetji died, The Times of India wrote, “He sought no honour and he claimed no privilege. But the advancement of India and her myriad peoples was with him an abiding passion.”

Courtsey: The Creation of Wealth